The Power of Artificial Intelligence (AI), Virtual and Augmented Reality (VR and AR) on Medical Imaging at GPU Tech Conference (GTC) 2017

This slide, like the picture below from InferVision (Chinese startup) are common with Indian and Chinese startups creating new interfaces generating reports (noting AI predictions) on the medical images.

This year’s GTC organized a healthcare track dedicated to applications at the nexus of artificial intelligence and healthtech. A number of workshops focused on applying machine learning algorithms using Nvidia hardware, Graphical Processing Units (GPUs), to predict the onset of early stage cancer detection, with many sessions analyzing other cancerous tumors in anatomical structures such as the lung, breast, and brain. Many sessions analyzed brain fMRI in particular as a means of advancing studies on various neurodegenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer’s Disease (AD).When you’re building a website for a company as ambitious as Planetaria, you need to make an impression. I wanted people to visit our website and see animations that looked more realistic than reality itself.

Below are some quick highlights from the sessions as well as few notes on Virtual Reality (VR) and Augmented Reality (AR) demonstrations and the implications of the dynamic user interface for medical research technical applications.

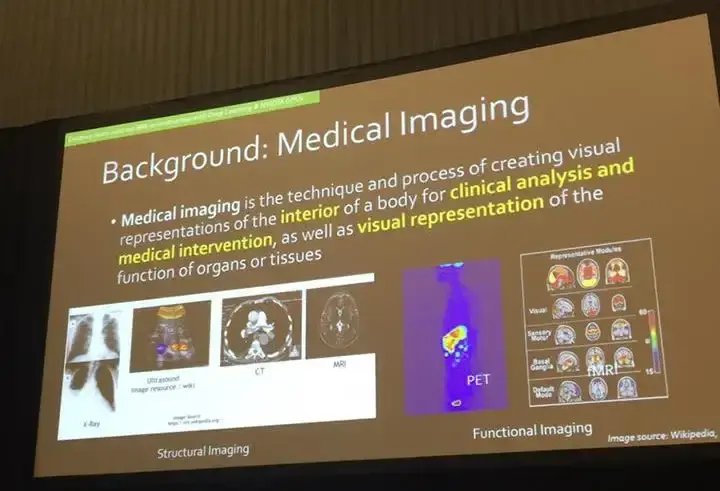

Researchers are able to take images from the various scanners used to see anatomical structures in the human body, enhance and augment the images, detect pathology , diagnose disease, and in some cases, even help with the other end of the spectrum, with treatment and prognosis as described in the picture above.

Challenges

Several workshops echoed the same sentiments as Le Lu, Staff Scientist of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) surrounding data quality (data size, annotations, data focii).

“Nevertheless, unsupervised image categorization (that is, without ground-truth labeling) is much less investigated, critically important, and difficult when annotations are extremely hard to obtain in the conventional way of “Google Search” + crowd sourcing (exactly how ImageNet was constructed).”

The traditional definition of “big data,” tends to be discussed in the analysis of millions to billions of users. However for researchers working in the health, medical, and biotech community, data, while rich, it is a common remark I hear, that researchers are limited with only so many datasets and are confined to a small number of patients and data sets while larger in scale (multiple images per patient).

Stanford University Professor Daniel Rubin, who teaches graduate level course “Computational Methods for Biomedical Image Analysis and Interpretation” discusses this struggle as well as the need for more intuitive Machine Learning (ML) tools that not many biomedical researchers who understanding computer programming would need to quicken the pace for medical research.

Similarly, Stanford University PhD candidate in Electrical Engineering, Enhao Gong, who presented “Enhance Mutli-Contrast MRI Reconstruction for Improved Diagnosis with Deep Learning Powered by Nvidia GPUS,” shared the same sentiments. His work discussed how the Nvidia GPU increased their pre-processing speed by 4000x and 100x for inference and entire reconstruction of MRI. Given the constant repetition in most workshops (as well as Nvidia Founder and CEO Jensen Huang) talking about the Moore’s law, the limitations in producing good hardware is not our biggest challenge, but in maximizing optimization from the data to algorithms and the applications we create.

Watch Jensen Huang’s keynote here.

If data continues to be siloed in specific hospitals (data sets remaining small in size), it makes it even more difficult for researchers and clinicians to maximize the benefits of machine learning applications on medical imaging. As said in the slide below, the data itself is focused on one particular Region Of Interest (ROI) (meaning one portion of an image focused on a nodule, tumor or some other specific in the image), and it is still not enough, as the majority of the data can be a whole image of a given anatomical structure.

Slide from Stanford Professor Daniel Rubins’ talk “Deep Learning in Medical Imaging: Opportunities and New Developments”

One of the other main challenges in medical imaging and machine learning for researchers mentioned is data quality (outside of high resolution images).

Le Lu’s session “Building Truly Large-Scale Medical Image Databases: Deep Label Discovery and Open-Ended Recognition” discussed the differences in size and scale from the typical well annotated ImageNet (Stanford University Professor and computer vision pioneer, Fei-Fei Li’s work) compared to the challenges many researchers, and those working at the national scale struggle with. Instead of millions or billions of users, the patient data is much smaller in less than 100,000 people with multiple images per person (CT and MRI). Contribute to the NIH open source dataset here.

In order to be more effective in applying machine learning on medical imaging to conduct feature extraction, there is a need for labeling given the lack of annotations by clinicians on datasets. In Lu’s session, he discussed how he built a large-scale dataset focused on chest x-rays (lung cancer), took the labels on the data on common disease patterns predefined by radiologists to generate a report for each image, which would result in disease an automatic detection/classification and disease localization. The images below show NLP and report generation in Lu’s application as well as another startup, Infervision on the GTC Expo Hall floor.

At the GTC Expo, Chinese startup Infervision’s user interface displaying a medical report on MRI https://techcrunch.com/2017/05/08/chinese-startup-infervision-emerges-from-stealth-with-an-ai-tool-for-diagnosing-lung-cancer/

While report generation is good (as seen in AI startups at GTC Expo, Infervision and in Le Lu’s talk), some of this data analysis is still limited, which is why even VR tools created by radiologists (which I will discuss toward the end of this article) attempts to change the workflow of researchers by viewing their data immersively almost like an 3D explorable explanation.

Nvidia’s software framework: DIGITS

Saman Sarraf, engineer and researcher also presented his work on Deep AD (Deep Alzheimer’s Disease) on how to predict with a high accuracy using Nvidia digits. You can read more in Saman’s IEEE paper here and on the Nvidia blog.

Here is the information architecture outlining the process by which radiologists undergo (a lot of time on data preparation and pre-processing) to begin analysis on patient data.

Sarraf’s work is that like many of all the other sessions I attended which handle the images, trains on a Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) model, and results in image classification that can help researchers.

Here is a quick video from Enhao Gong’s workshop which explains CNN in a way that it visualizes similar techniques to smooth out images and conduct feature extraction.

Outside of the majority of the talks that talked about neural networks focused on supervised learning and image classification, one of the most interesting sessions I attended, Robert Zigon’s talk on “GPU Data Mining in Neuroimaging Genomics,” showcased the intersection of machine learning, bioinformatics, biostatistics, and neurology with his analysis on the correlation between the attributes of the MRI voxels and single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP) in DNA sequences of Alzheimer’s patients. The User Interface (UI) heatmap gives a high level overview of the relationship between gray matter density from the MRI and SNP genotype. As the user hovers over each segment of the brain, in real-time, is able to see the brain and voxel by voxel the correlated SNP to each part of it.

Other Related Studies

Much like the use case focused on image reconstruction on anatomical structures presented by Enhao Gong, who discussed Arterial Spin Labeling (ASL) to quantify perfusion maps (cerebral blood flow), I was happy to find that one of the trainings advancing research on heart disease utilized fMRI data to measure blood flow in the brain during the “Deep Learning for Medical Image Analysis Using R and MXNet” presented by Nvidia. This workshop showcased Amazon’s the deep learning framework MXNet to train a CNN to infer the volume of the left ventricle of the human heart from a time-series of volumetric MRI data. While not focused on neurodegenerative brain disease, this workshop showcased how different types of applying machine learning algorithms on other types medical imaging could advance medical research in other areas, a more holistic approach when it comes to thinking about the human body as a whole, and not a single organ or anatomical structure to be study disconnected from the rest.

Virtual and Augmented Reality demonstrations

One of the best VR demos I tried was from a Swiss company, Virtual Radiology which reminded me of University of Toronto’s work, only high resolution, in-color. See here for video of University of Toronto’s demo (TVASurg Medical Imaging VR Module) with black and white MRI.

Christof von Waldkirch, Virtual Radiology CEO, a radiologist by training showed how researchers are able to make slices and adjustments to the image. This for me, was hands down one of of the best VR demos I have seen from healthtech space in HTC Vive.

While again, not focused on brain imaging, immersive and emerging technologies of VR, AR are intersecting with healthtech and AI in new and different ways. Virtual Radiology’s co-founders like many of the presenting researchers I spoke with (as well as myself) all experience the same problems in image processing, having trouble with decreasing the noisiness of the the MRI (image clarity), and taking different approaches beyond smoothing are a large part of the data preparation pipeline extensively before finding any insight into the data).

Y Combinator-backed Augmented Reality company, Meta, whose CTO Karri Pulli (former Nvidia researcher) presented Spatial OS and Meta’s AR design guidelines briefly during GTC, Meta’s CEO, Meron Gribetz on the 3rd day of GTC presented an AR demonstration at Stanford’s Center for Image Systems Engineering (SCIEN) Augmented Reality Workshop. .

Meta’s design is grounded in neuroscience. Referencing Dwight J. Kravitz’s seminal work in 2011, Gribetz notes how humans have for the last 50 years of computing only been engaging in one of these two visual systems (dorsal pathway as opposed to ventral pathway). Traditional non-intuitive flat user 2D interfaces have trapped our thoughts and interactions into the confines of the screen (mobile, desktop etc.) and does not optimize the use of the ventral pathway which understands objects in relation to spatial relationships, what augmented reality has the potential to do. He explained how humans only exercise particular areas of the brain when interacting with some of the limited Graphical User Interfaces (GUIs) we have created (like command line).

“The part of the brain that is parsing symbolic information and language, these are areas that represent fairly small volume of the brain, and we were utilizing them alone. As we latch on to multiple cortical modules, as you interact more and more with the mind, you approach this asymptote with zero learning curve, the computing paradigm will be like ‘pinch to zoom’ across whole operating system.”

Gribetz gave a short demonstration of Glassbrain, an interactive 3D object of the brain and explained how Professor Adam Gazzaley UCSF lab representing the white matter tracts. He used an EEG scan of the EEG cap of Grateful Dead drummer as he played a drum solo. They overlayed color on DTI (Diffusion Tensor Imaging) to create it. This was at Stanford’s AR Workshop on day 3 of GTC). See YouTube video below.

He referenced Leonard Fogassi who discovered F4 in the brain, which creates depth maps of objects that you are touching and where your hand is near the vicinity of the object.

“As I move my hand around this brain, I am creating an internal 3D model inside of my mind’s eye of this object. If any part of peripheral nervous system, the palm has the highest condensation of of neurons. We have highest degree of freedom and accuracy of control if we touch holograms directly. We understand objects more deeply why we do so. This is why we advocate not using controller or mouse which separates two x y planes from each other and just separates you further from this fine tune many degree of freedom control. “

As Glassbrain and Virtual Radiology’s high resolution, colorful, and interactive GUIs are only the beginning proof of concept that demonstrate how we can begin to rethink how medical researchers can interact with their user interface beyond plain, black and white, flat design, or drab reports to get our mind flowing.

Ending notes

The fields of medical imaging and machine learning have come a long way since the explosion of AI in recent years, and still struggle with various challenges, many of which are non-technical and have more to do with data collection and data quality. The fusion between using AI on current 2D interfaces (dominant in most of the discussion here outside of VR and AR) with the creation more open source software (tools), open data, as well as intuitive user interfaces (VR and AR), medical research can advance with AI. Virtual Radiology in VR and Meta in AR is only a few examples of how viewing medical imaging (even without a ton of AI) is changing the user interface to create new paradigms of analysis. I’m excited to see what new intersections between these emerging disciplines can do to further advance research in medical technology.